As many of you know, I am Associate Editor for a small publishing house. I love this job more than agenting, more than consulting–I really enjoy it. One thing I find, though, is that there are some pieces of advice I seem to give over and over. I thought that I’d make a page, and add to it later, if necessary, with suggestions I commonly make. I can point writers here and hopefully they will understand. So, if you have questions, let me know and I’ll make things clear. I know the list will grow. *Updated 10/25/2023

Formatting

First of all, I want to talk about formatting your manuscript. And no, I don’t mean .02368 in margin detail. These are things I see over and over again. And it’s not a problem that they exist, but you, the author, should know how to do these things in your future manuscripts, because they exist to make your life easier. (Most of my authors write in Word or a comp program, and I edit in Word, so this is the method I’m using to illustrate.)

1] First line indent and spacing– In a Word document, you can operate these functions from the same place. (Do NOT manually tab your indents or press “enter” after every line, or press repeatedly to the end of the page.)

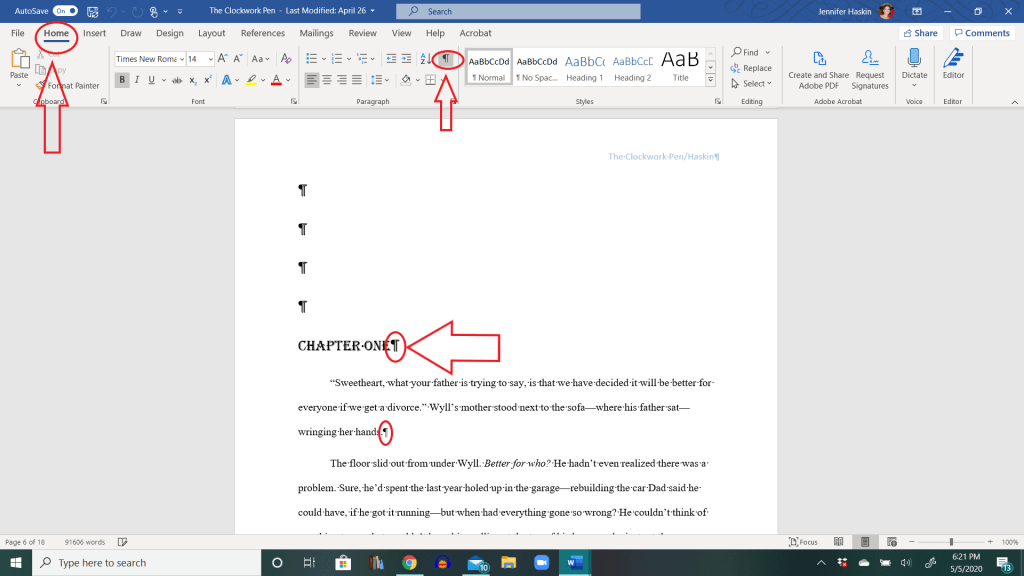

–Whenever you start typing a document, type in a few lines and stop. Next, go to the Home tab in the menu ribbon above the page and look in the Editing box, then click to Select All.

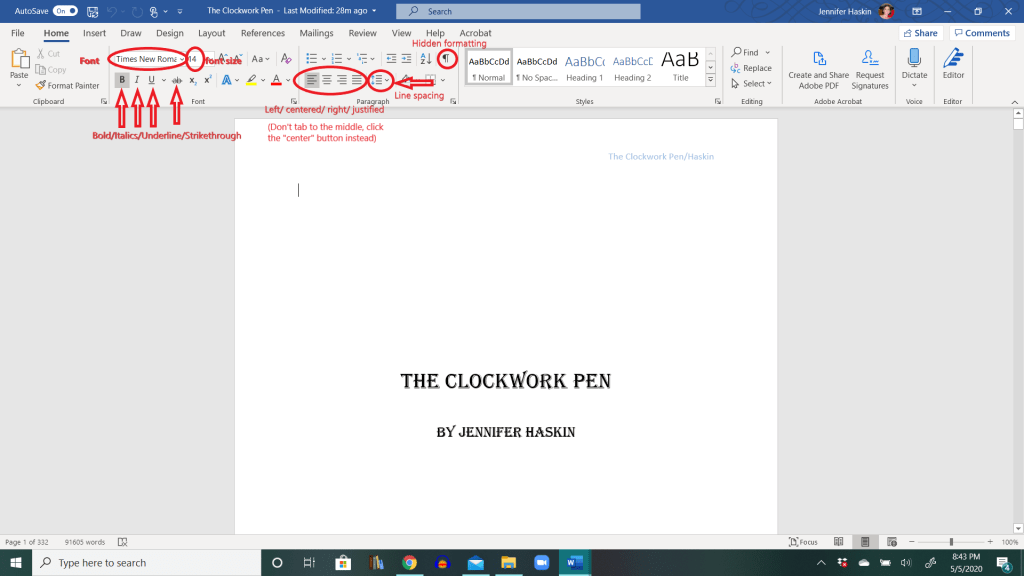

–Now, while your text is highlighted, stay on the Home tab, and go to the Paragraph box. Where the four little lines with arrows are, click that box (pictured below) and choose your line spacing. I usually choose 1.15, and at the bottom, make sure it says “Add space” before and after paragraph. If it says “remove space” then click it again so they both say “Add space.” This will remove empty lines between your paragraphs as KDP suggests.

–THEN, with your text STILL highlighted, stay on the Home tab, and go back to the Paragraph box. This time, click on the tiny box in the lower right corner, and a new menu will pop up (pictured below).

–In the menu, in the first section, click Justified or Left. This will make your text start on the left side of the page, but with left, the end of each line will be varied and with justified, the ends are even.

–In the second section, make sure the left and right boxes say 0″. This way, your text will go all the way to the margins like it’s supposed to.

–Then, on the right where it says Special, click the arrow and select First Line. Now, all of your paragraphs will be indented. (If you are typing later and you press enter but the next line does NOT indent, just come back to this place and click First Line again.)

–In the last section, make sure the before and after boxes say 0 pt. This will have no blank spaces before or after each paragraph.

–Click OK.

You’ve just done half the work of formatting before you start, and it will keep your writing uniform and easier to read as you type.

2] Page breaks–

After each chapter in a book, you need to make a “page break.” This ends the text on that page and begins the next text on a new page. (So you don’t have to press “Enter” a thousand times and if you move anything, it won’t mess up all the other pages.) You can then add to or subtract from the first chapter, but no matter what you do, the next chapter will be on the following page. Does that make sense? I hope so.

You will make page breaks at the end of each page in your front matter (title page, copyright page, dedication, table of contents) and your back matter (acknowledgments, about the author, also by the author, etc.), and at the end of each chapter. You add a page break whenever you want something to start on the next page.

The way to do this is to click at the end of your story or a line or two down (it doesn’t matter unless you are close to the bottom of the page). Then go to the Insert tab, in the Pages box, and click on Page Break. That’s it. No more pressing enter a thousand times and having to fix all the other pages!!

Don’t do this unless you have the formatting marks on so you can see where the page breaks are.

Now, when you do this after the fact, as in this book, once you click on Page Break, all those extra “enters” will move to the next page, so you’ll have to delete them to get the text back up to the top. You’ll have to do this for each story.

In your next work, just do these steps as you type, and it makes life much easier. :^D

If you have your paragraph marks and format symbols visible, you can see the “page break,” but otherwise it’s invisible.

Wait, you say. What if I do want to see that hidden formatting to know something? Easy.

To see your formatting marks when writing (I always write with the formatting on to see if I have the right number of spaces and lines, and to see the page breaks), go to the Home page in the menu bar above, look in the Paragraph box, and find the button that looks like a Paraph and click it. To turn formatting off, click the same button again.

A paraph looks like this:

3] Another thing you don’t want to do manually is enter your header/footer or page numbers. I add my header to the top right with my title/last name, and I put the page numbers on the bottom right.

Page numbers and header/footer– From the “Insert” tab, look for the “Headers and footers” section. If you click on “Page numbers” it gives you the option of where you want to put the number. In the same section, you can click to add your “Headers and footers.”

4] Home tab– Get to know the icons on your “home” tab. this is where you find the “bold,” “italics,” “underline,” and “strikethrough” buttons, as well as the font and font size. The text justifications are there in the “Paragraph” section. Do not “tab” to the center, place your cursor before the word and click the “center” button. You can also click the “line spacing” icon and change from single to double spaces, etc.

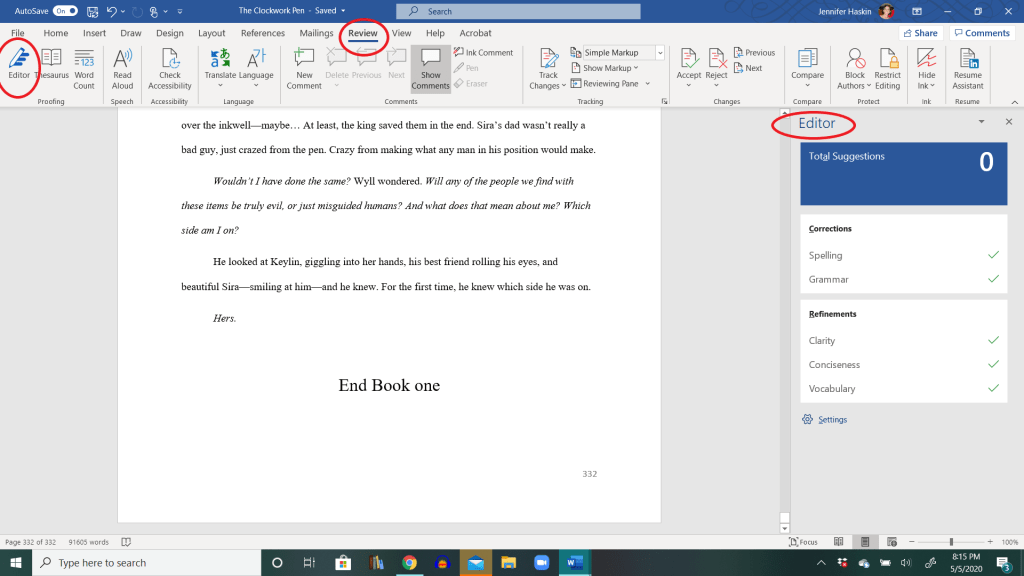

5] Edit/ spell check– This one is on the “Review” tab, in the “Proofing” section. Click on the icon that says, “Editor.” A box will pop up on the right. Just click each section and follow the prompts.

A few odd notes for your manuscript:

1| Spell out numbers under 100.

2| Foreign words always go in italics.

3| If you are writing a.m. or p.m. you must use a numeral

4| Internal dialogue (direct thoughts), dreams, visions, thoughts, words the character reads–basically, anything that happens in the character’s head–(or the character speaking directly to the reader) all go in italics.

5| Most editors hate exclamation marks. But I find they are sometimes necessary. However, my rule of thumb is to only use an exclamation point when the speaker is actually shouting.

6| Punctuation goes inside the quotation marks. Always use double quotes unless you need quotes inside your double quotes, then they are single. Otherwise this key, ‘, is just an apostrophe.

7| Are you outside of the US? Tip: If you are going to publish to the US market, you’ll want to use the American spellings.

8| “Just” is a weak word and one you want to cut from any book if you can. “Just” is used in some cases as a descriptor for how hard you are “trying” to do something: A. (I just tried to do a good job). Or it is used to mean that you “simply” try to do something: B. (I just made dinner, nothing special), OR to emphasize that you are striving or struggling to do something: C. (I just wanted to tell you how I felt).

Take the sentence, I just try to describe him. How else could you say this?

In this case, it’s like using adjectives to describe an action. It’s better to cut the adjective and think of a stronger word. So, in this case, you have three options:

A] Delete “just” and leave the sentence alone. I try to describe him. I am leaning toward this version.

B] In the case of describing in basic terms, I would say something like, I describe him simply.

C] I strive to describe him. (This is also a pretty vague sentence. Are you describing their appearance, their character, their personality? What are you striving to describe? Tell us that.)

D] Or I struggle to describe him. Now, this one doesn’t have to be as descriptive because you are telling us that you can’t describe him, so it doesn’t matter. We see the other person as an enigma. (I actually prefer this one.)

Take the sentence: I’ve been trying to describe him.

“Been trying to” is a weak position. That sounds like someone asking a person if they did what they were asked, and they answered, “I’ve been trying to.” Did they or didn’t they? And if they are trying, how hard are they trying and are they succeeding?

Let’s make it a sold statement.

[The reason we like solid statements instead of -ing words has to do with the powerful nature of your statement. For example, which makes a more powerful statement:

I am trying. OR

I tried.

The second one tells us you did the thing you are professing. Sometimes, trying to is necessary, so don’t cut it out everywhere, but ask yourself if a bold statement would add or detract from the text.]

9| –A peak is the pointed top of something.

–Peek is to look quickly, typically in a furtive manner.

One of the ways I tell people to remember this is: the A in PEAK is like the top peak of a mountain, and the two E’s in peek, are like two hooded eyes peering (peeking) out at you.

10| This one is very important, and I see it done wrong on many occasions. The speaker of a piece of dialogue MUST be the subject of the dialogue OR action tag that follows it:

For example:

“Hey! How’s it going?” Suzie asked, placing her lunch tray on the table. (dialogue tag)

“Pretty good.” Chris pulled a sandwich from his lunchbox. (action tag)

“Did you pass that chem test?” Suzie broke her brownie in half, offering half to her friend.

“Nah. I didn’t even study,” Chris said, taking the brownie half, and tossed Suzie his cheetos.

Each line of dialogue above has either a dialogue tag (Denotes who’s speaking with “said” or “asked.”), or an action tag (also denotes the speaker but gives an action rather than assign the speaker only). For an in-depth look at tags, click here. Make sure each speaker has their own line to respond. Never have two characters speaking in the same paragraph.

But it would be INCORRECT to say:

“Hey! How’s it going?” Suzie asked Chris, placing her lunch tray on the table.

“Pretty good.” Suzie watched Chris pull a sandwich from his lunchbox. (This is Chris’s turn to speak. He should be the subject of the tag. In this case, Suzie has the verb in “Suzie watched,” so Suzie is the subject. Make sense?)

“Did you pass that chem test?” Chris took half of Suzie’s brownie while she asked her friend. (Here, Suzie is asking the question, so she again needs to be the subject with the verb. Here it is “Chris took” and even though it says Suzie “asked her friend,” Chris is the subject, it sounds like Chris said it. This confuses readers.)

Craft

My writing advice, having done this a few times now, is to make something similar to an outline first. I call it a “sceneology.” I decide what “scenes” I want in the book and list them in order of how I want them to occur. It can be as simple as “She wrecks the car and meets Tim,” to a fully fleshed out concept with details. I write each “scene” descriptor on an index card and put them in a ring together. (You can get ringed note cards already made at the office supply store.) You can take out things and add or reorder your cards as often as you want. And then, when I know I have a good story with rising action, and a climax, and no plot holes, I sit down and flip to the first card, then write that scene. When it’s done, I flip to the next card and write that scene, and so on. It’s so much easier to write and to get creative when you don’t have to think of the plot. You know it’s all ready, you just have to write out your scenes. This helps me so much. I encourage you to try it. Just tell yourself, today I am going to plot, and make some note cards. When it gets down to the writing and you have a whole ring of scenes to write, you just tell yourself, today I write one scene…

Here’s my advice on chapter hooks: Each chapter is often seen as a scene. When you start the book, you want to start in action. Say a scene has four parts: 1-the beginning, 2-the action starts, 3-climax, 4- resolution. When you start a book, you start at number 2. Most authors finish that scene with 3 and 4, and then end the chapter at that natural breaking point. BUT I say then, instead of quitting, you begin the next scene, and just when it gets interesting–BAM!–end the chapter. The reader, already invested in that scene, cannot stop reading, because they need to know what happens. See, people have a need to finish the chapter before they stop reading, but they have an equally strong need to finish the scene before they stop. So, they say, “I’ll stop at the end of this chapter,” but then they can’t. When that scene finally ends, they are well into the next chapter, and they can’t stop. They say, “Okay at the NEXT chapter I’ll stop.” But as long as you keep on writing 2, 3, 4, 1, they can’t put the book down. You don’t even have to write chapter hooks because the reader can’t stop themselves from continuing.

My latest books all have the reviewers saying, “I couldn’t put it down…” And that is why. That’s the ultimate compliment to an author: “I read till 2am!” So, resist that desire to end the scene and the chapter in the same place. :^D

When it comes to dialogue tags, use “said,” or “asked,” as much as possible. “Said” is considered a non-word that your brain doesn’t actually read. It is skimmed over and understood and doesn’t halt the flow of conversation. However, using other dialogue tags causes the reader to have to slow down and “read” the words instead of “understanding” them. So, use “said” to keep the pace in your dialogue. To add variety, it is tempting to use words like “assured” or “joked” or “informed.” It was used widely in an older style of writing that contemporary English says is redundant. That’s why some argue that the only tags to be used are “said,” “asked,” and maybe “replied,” or “stated.”

You want to let the conversation stand for itself and trust the reader to know what they are doing. You wouldn’t say,

“Why did the chicken cross the road?” he joked.

Because we already know it’s a joke. We read it. The only time I would explain a piece of dialogue is if it contains info that the reader does NOT know. Like:

“I found my things in your room, did you take them?”

“No,” he lied.

In that case we may not know if he did or not and this lets the reader know he’s lying, or the other character thinks he’s lying. But if the character is reassuring someone, you don’t need the tag to say, “He reassured her.”

In dialogue tags as well as action tags, the subject of the tag needs to be the speaker of the dialogue.

**Dialogue always ends in either a comma, question mark, or exclamation point–but not a period–if there’s a dialogue tag.

You don’t NEED a dialogue tag of “he said” or “she said” if you have an action tag. (You don’t always need either, but do remind us who is speaking every few lines of dialogue, or if there are more than two people conversing.) And this can be done with an action tag. For example:

“Hi.” Jill rested her head on the doorjamb with a sniffle.

“I heard you weren’t doing well, so I brought you some soup.” Barbara held out a thermos with one hand and a plate with the other. “I made these cookies, too. Your favorite.”

Jill brightened and took the proffered gifts. “Thanks for stopping by, Barb. I appreciate it.”

The action tags tell us what is going on without telling us they “said” anything. Notice, with an action tag, the dialogue does end in a period.

Some situations where it might work to use a descriptive word with dialogue is if it adds to the readers understanding of the scene.

If the bad guy says something nice, you could have them “say” it, or “sneer” it, or “gush” or “snap.” You aren’t describing what he said or did, but his attitude about it. It shows the reader that he is being complimentary, not disbelieving. Or that he’s making fun of the other speaker. It shows his motivation and delivery, and it makes the reader see the scene better.

Instead of “ask” I have seen writers use “question,” but the only time you use that is if you are questioning someone as in police questioning, or in a mystery. It denotes one person asking many questions of another party in a demanding tone. Not usually what you mean when Mom “questions” her daughter about her regular day at school.

When writing character actions, this comes up often. A head “shake” is from side to side, generally a “no” answer. A “nod” is up and down and denotes a “yes” answer. Some authors will say that a character “shakes” their head in a yes answer. Or that they “nod” their head from side to side. In my head, I see a person touching their left ear to left shoulder and then right ear to right shoulder and back again. It’s comical, but I know that isn’t the intention. So go with “shakes their head” for no, or “nods” for yes.

You may find in your writing that you include “begins to” when a character does something, and that only works if someone is supposed to begin an action that will be stopped in the middle. Otherwise, just make them DO the activity. He doesn’t begin to drive off. He drives off.

As far as POV (point of view) comes into play, each scene needs to be in ONE person’s perspective. If you are going to change perspectives within a scene, or chapter, you need what’s called a scene separator. I use this one:

~*~

Center it on the page and then you can change scene and/or POV. There is a style of writing where you can switch POVs within a scene, and it is called Third Person Omniscient Subjective, but in this type of book, which used to be wildly popular, you cannot know the direct thoughts of the characters. For example, you would NOT say the following:

He drained his cup. What is taking her so long? It had already been a bad day and Philip just wanted to pay his bill and go home.

Why is that guy staring at me? The waitress took all her dishes back to the kitchen and went to help him, she couldn’t imagine that he was done already.

The words in italics are direct thoughts from the characters’ minds. Now I did two things here, I switched POV, and I gave them direct thoughts. If we were staying in Philip’s POV, we wouldn’t know anything the waitress thinks. In a normal third person POV, the second paragraph would say something from Philip’s perspective like: He watched the waitress taking a tub of dishes back to the kitchen. She threw him a glance on her way out the door and was soon back with a curious expression.

However, even though I have gone to her POV, the whole thing could work in a Third Person Omniscient Subjective if I took out the direct thoughts. Then it would read something like this:

“He drained his cup, wondering what was taking the waitress so long. It had already been a bad day and Philip just wanted to pay his bill and go home.

Confused by his stare, the waitress took all her dishes back to the kitchen. She washed her hands and went to help the frowning customer, though she couldn’t imagine that he was done already.”

It’s a very subtle difference.

You may or may not have heard of “Chekov’s Gun” theory. It states that if there is a gun on the mantle in act one, it had better go off by act three. Meaning, do not add exciting or threatening things to the story, just for the shock value. If you put a gun in there, it had better be because someone is going to use it. Don’t introduce characters in the beginning that will have no bearing on the story from the first chapter on. They don’t have to appear again, but there must be a lasting reason why they were important enough to be there. Maybe they light a fire in the protagonist, which is what carries them throughout the story or begins their journey in some way.

I admit I am hardest on the first few pages. I often tell my authors, do not be dismayed by the amount of comments on the first few pages, the rest of the manuscript generally has fewer comments. Those first pages are the most important in your book. You don’t want to lose a reader at any time, but if you lose them at the beginning, they never even get started. But if you get a chance to look over these suggestions and make fixes to your own manuscript before having it edited, all the better.

Ah, here’s one. Ellipses (an ellipsis is three periods in a row) have a space before and after them if they are in a sentence, and taking the place of a word, or a pause in the sentence.

For example: “They were gone for, ah … several hours.”

However, if the ellipsis is at the end of a sentence, as though the character is leaving off words, there is no space.

For example: “We think they might be into some trouble…”

Dashes do NOT have a space between words–in fact, just hit the dash twice and keep going.

If you’ve been a writer for more than five minutes, you’ve heard the phrase, “Show, don’t tell.” This one simply means that you never want to TELL the reader how the character feels but show them. For example, you wouldn’t say, “She felt terrified.” Instead, you would use words that describe that fear, that tell us how that fear is affecting the character.

i.e. “Sweat beaded along her hairline and the back of her neck prickled like a hundred tiny needles in her skin, the acid in her stomach crawled up her throat and her whole body trembled in fear.”

Anytime you find yourself telling the reader about something, stop and ask yourself if this could be described more specifically. That goes for situations as well. Rather than saying the room was “dark and cold,” this is where your writing chops come into play.

You might say, “She couldn’t see anything in the inky shadows, merely ominous shapes looming around her. The temperature caused her fingertips to numb, and the shells of her ears tingled with early frostbite. She blew on her hands to warm them, waiting for her eyes to adjust to the darkness.”

The idea is, you don’t want to tell readers what’s going on. You don’t want to explain what’s happening in the story and why they should care about it. You’re not giving a book report. Your story needs to stand on its own. In the first draft, don’t worry too much about this, and it’s okay to break this rule sometimes.

Mainly, this is about the non-visible things: character motivation, feelings and emotions, a character’s backstory. They can be difficult to show, which is why telling is easier:

He was angry.

He had a pet dog as a kid and that’s why visiting the pound made him emotional.

Telling readers things skips over the scene, it’s an information dump, not story: people can’t SEE information, so while it may help them understand what’s going on in the story, you always want them to be able to see what’s happening. A good test: if you can’t draw what’s happening, it’s telling. Try to change it to something real, something you could see or draw.

He approached the cage with trembling fingers, then clenched his fist as he saw a tiny Pomeranian in a rusted cage, with an empty bowl. It reminded him of Sam, the dog his father brought home when he was ten. The one that got hit by a car after he forgot to shut the gate. He hated dog pounds.

Notice how much extra conflict I snuck in here: the empty bowl, guilt over leaving the gate open.

Sometimes, you’ll need another character to draw out the information, so the character isn’t just thinking out loud.

He approached the cage with trembling fingers, then clenched his fist as he saw a tiny Pomeranian in a rusted cage, with an empty bowl.

“What is it?” she asked, placing a palm on his arm.

It reminded him of Sam, the dog his father brought home when he was ten. The one that got hit by a car after he forgot to shut the gate.

“Nothing,” he said. “I just hate pounds.”

Here, we’ve introduced more conflict, because–while it COULD have been a place for the character to open up and be vulnerable, he doesn’t.

Common Mistakes

As an editor, there are common weaknesses and mistakes I see if fiction all the time. Here’s a list to watch out for.

Pacing – it’s good to start with action or conflict. An old writing trope is “start with a dead body.” But if you do start with the big stuff, your characters need to be reacting. As soon as the pressure is off and they’re safe, they should have their guard up and try to figure out what happened. (So you can’t have light teasing, flirting, casual strolls through the park, getting to know each other small talk, confessions of childhood trauma, etc).

Backstory – generally, we don’t need it. Get the ball rolling. Later, when the characters trust each other, you can have them share their vulnerabilities, and motivations. Especially for WHY they must do something crazy, when it’s needed. However, you also need to quickly reveal the immediate backstory: how characters came to be where they are; what they are trying to do right now; where they were before shit hit the fan.

Story vs not story – every scene must have a purpose, and there are three:

- something new happens

- the characters (or readers) learn something new

- the character must react based on new information (new plan)

- the characters must try something new (execute new plan)

Notice the common thread? NEW. If the scene doesn’t move the story forward, it should be story (it might just be a transition, getting from A to B, in which case, skip it).

But… it can’t just be “hey let’s get a change of scenery and go to my mansion” because:

Conflict – conflict drives story. If there is no conflict in a scene, it’s dead. Nothing should ever be fun, light or easy (unless big shit is about to happen). It’s actually great to have some slow, thoughtful scenes, and focus on the relationships between the characters … just before one is killed or forced to betray the other (happy scenes are a foil for the bad things).

You don’t want to keep your foot on the pedal ALL the time, but there should always be conflict. Sometimes this can be done with…

Suspense – It’s tricky to get this right, but suspense is having the protagonist and reader being worried about what’s going to happen next. They can’t be CONFUSED about what’s going on, some things need to make sense, but you can show weird or strange things happening without explaining everything right away. Suspense is done by presenting new information that makes the protagonist doubt, question or wonder in a fearful way. It should always have a hint of danger. Is this safe? Can I trust him?

Clear objectives – the main character must have a clear goal and objective; then make it really hard to achieve – add conflict, barriers, challenges. Make it difficult. For the first 1/2 of the book, the character is reeling as everything is taken away. They’re trying to get their balance, trying to get back to normal; so they’re reactive. For the first 1/4, they refuse the circumstances and call to adventure; for the second 1/4, they’re on the new path with no way to get home again, but that’s still their goal. Something happens, they react and plan, then take a new action unsuccessfully. Sometimes more bad things will happen before they execute the goal. Sometimes they succeed but it doesn’t matter because they were wrong about everything. Sometimes they succeed but something else even worse happens as a consequence.

Emotional stakes – they need something to do, and it has to have big, clear stakes (i.e. what happens if fail) and characters need to be emotionally motivated (background, to risk danger). They also need opposition to stop them.

- Why does this matter to character, what happens if they don’t take action (personally)

- Why does this matter to everyone (global stakes)

- Who is trying to stop them, and why (villains, antagonists, traitors, etc)

- Life or death–stakes should always seem like life or death to the protagonist, even if they aren’t really. They represent a threat to the self: the protagonist’s former self will be forced to die or change; they’ll have to give up their identity, what they’ve always wanted. Even if it’s a contemporary romance or high school drama, they should care SO MUCH about what happens that failure feels like death.

Thoughts to self – don’t have a lot of witty reflections or punctuated comments interrupting the actual story. Generally, thoughts should be exposition, not articulation.

My, oh, my, I thought. That’s one crazy lady! vs. I wondered if she was crazy.

If you have internal thoughts, for punctuation it’s best to have them in italics. She must be crazy. And you don’t need to add “I thought.” These internal thoughts are in first person. You wouldn’t think to yourself, If she messed up, what would happen? No. You would think, If I mess up, what will happen? Notice, the thoughts usually change to the present tense, as well.

Also, don’t use thoughts to describe or summarize what’s happening.

AND: be careful not to use big words or hyperbole instead of real description. “Incredibly big” is still just big. What does it look like? “Tremendous victory”–what does it look like? They suffered “devastating losses”–what does it look like?

Too much emotion – one of the main writing mistakes I see new authors make is having their characters get all weepy and emotional, then be cool and charming, then laugh hysterically until they cried. People don’t act this way (if they do, they’re annoying and probably psychopaths). Most people hold their emotions inside, especially with strangers or people they don’t know. ALSO, the character’s challenges need to mount throughout the story. If you have them weeping in the first chapters, 1. readers won’t like them and, 2. it lessens the emotional impact of the story.

As tension and conflict build, eventually there will be a “dark night of the soul” scene where they break down and give up. But before we get there, they should be trying to hold it all together. It’s fine to have a few touching scenes, and a lot of emotional angst, but it shouldn’t cause a meltdown.

Dream sequences or anecdotes–long stories or dream sequences should mostly be cut, unless they very clearly help the protagonist figure out what to do next. Maybe a teacher or ally tells them a story to motivate them. In a recent book, I have a long virtual reality scene. It’s awesome, but it’s not real. The stakes aren’t real, so while it’s visually cool, it also doesn’t matter. It’s kind of okay because she leaves it with a confidence boost that helps her take action: something changed, and it’s necessary to the plot.

But if it’s a long story, and something that didn’t really happen, it’s better to skip it.

Making characters likable–if your character is mean, selfish, spiteful, or stupid, readers aren’t going to like them. It’s okay to start off with someone who’s not perfect, but they should uncover their more admirable qualities through the story (you also never want to start with someone who IS perfect, or awesome, or badass–unless they’re about to get destroyed by circumstances and lose everything). You need to make characters likable immediately–or at least relatable. The easy way to do this is to make them capable–they deal with threats or challenges coolly and creatively. They’re composed and clever. And they’re also responsible–they’re taking care of someone else. They stand up to a bully, save a child or a kitten, pet a dog, put food on the table for their crippled mother.

Too many details–readers should see what we see; but they should only see what’s relevant, and what matters. If you show a gun, it should be used later. If you spend a paragraph describing an old woman in the market, she needs to be critical and important. A character shouldn’t notice random weird things or characters if they don’t matter to the story.

Conversely, the more something matters, the more you need to describe it in detail so readers remember it later. You can:

- plant red herrings–things that seem like they might matter but ultimately don’t or,

- lightly touch on things so they’re established, but don’t dwell on them so readers are surprised.

Also, description always belongs at the FIRST instance–the first time they arrive at a new setting or meet a new character. Be careful not to add a more detailed description later (unless, the first time was a rushed action scene–in that case, the character won’t slow down to look at everything; then the second time when things are calm they may notice the details).

Don’t focus on the banal or trivial stuff–the teapot boiling … unless it’s about to become a weapon to ward off a home intruder.

Pulling rabbits out of hats–you can’t magically offer solutions to problems after you’ve come up with them. If you find a problem: “why would this happen” or “why would my character do this” you can’t just quickly interject an answer to solve it. Usually this stuff gets figured out in the editing process; find a problem, invent a solution, but then find a place to put the solution earlier, so it’s casual and already established, so it doesn’t look like you’re just making stuff up to fix your plot holes.

Wordiness–sometimes called “purple prose”–and unfortunately, what many authors think of as “good writing.”

“Kill your darlings,” means the prouder you are of your clever sentences and word choice, the more likely you need to cut it. Pretty writing stands out and draws attention. It can support a story, but it can also be distracting. It makes readers pay attention to the writing, not the story. Don’t use words readers will have to look up. Don’t speak in foreign languages to show off your knowledge. Don’t spend three pages on the history of civilization (unless it’s essential to story, and even then, cut it down to a few paragraphs). Use the LEAST amount of words you can to describe what happens. It’s best to sprinkle in descriptions with a few words here and there.

Unresolved issues–in the beginning, something weird or unusual happens. Readers and characters will want to know why, as soon as possible. That should be the main story driver. You can’t distract readers with other things until you’re ready to give them answers. They need to know what’s going on, what the story is about, who the antagonists are, what they want, how the main character is involved. You can withhold answers and build suspense for a little while, and you don’t have to do a full reveal until later, toward the end, when the main villain puts everything out on the table with a victory speech (hero at the mercy of the villain scene … not in every genre, but generally a full understanding of the antagonistic forces occurs just before the hero figures out what they need to triumph).

Melodrama–there is almost never a reason to use “?!?” or “!?!” or “!!!” in any book. Even “!?” is questionable. It’s lazy writing: punctuating the surprise instead of actually showing it. If you need anything more than a single exclamation point or question mark, you need to revise the scene to actually make it exciting and make the conflict and tension real.

Repetitive gestures–you need to break up dialogue with gestures, but be careful about getting into habits. Search for how many times your character smirks, crosses their arms, leans against a wall, rubs their chin, etc.

Adverbs–Okay in small doses, but generally there’s a better way to say things that with an -ly word.

He laughed hysterically, is telling. You can still use it, instead of describing exactly what laughing hysterically actually looks like, but if you’re using too many adverbs then you aren’t actually describing what is happening in your story, you’re just planting speech cues to help readers fill in the blanks.

Picturing the scene–I try to imagine a picture, like a still-frame photo, of each scene. If the two characters are sitting in a wood-paneled home office at night, the moon shining through the window, reclining in two highback chairs before a roaring fire, with cups of steaming tea, and a dog sleeping on a rag rug on the floor, I see the snapshot in my mind, and as I am giving the dialogue and fleshing out the details of the scene, I sprinkle in little bits of this description so that the reader, upon reading the scene, can also picture it. That is how to sprinkle in description without a big info dump listing what the scene “looks like.”

Very–if something is “very good” there are dozens of better words you can use instead. This can come later in editing though, just keep it in mind.

Typos are the easy stuff–it’s easy to fix typos, punctuation, or clunky sentences later, but it won’t fix the actual core issues (paying for editing will not make your book more commercial if readers don’t want to read it). The problem is, even an amazing developmental editor can’t fix all of this for you. They will point out the problems and suggest fixes, but you may need to do serious revising to get it ready for polishing.

In the first draft, we just try to put down WHAT HAPPENS. In the second draft, we focus on WHY it happens (character motivation). In the third draft, we focus on HOW it happens (what it looks like, and stoking the emotional angst). All of that needs to happen before we should even begin to worry about the actual words.

Tenses–I am assuming you know most of this, but I’d rather be clear, so I will explain the tenses:

Present tense says: I am going to the store, and I’m going to call John afterward.

Past tense says: I went to the store, and afterward, I called John.

**A manuscript must be all in the same tense, either past or present, not counting internal thoughts and dialogue.

Semicolons and ellipses, should be used sparingly in American writing.

This and that–Another sentence issue is using the words “this” and “that.” I often see authors use “this” instead of “the.” This man went to this new place he heard about. And in most instances, the word “that” can be cut; however, this is not always the case. To know for sure, if you read the sentence without the word “that” and it still makes sense, cut it. I read the book that he was writing, can also be said, I read the book he was writing. So, you would cut “that.”

The use of -ing words–Beware of saying things like, “I was going” instead of I went; OR, “She was doing work” instead of She worked; OR, “They were moving” instead of They moved.

It is still technically past tense, but -ing words are supposed to be used as an action if two things are happening at the same time or one thing is happening and gets interrupted. As in: She was going to go to the store and then going to the library. Or He was shaving when the doorbell rang.

Take a sentence that says, “…putting resignation on her face and shrugging her shoulders…”

(Notice the -ing words? In the past tense, you want words that end with “-ed” instead.)

So that becomes, “She looked resigned and shrugged her shoulders…”

Sentence structure–There is a difference between the sentence structures of English and other languages (for those authors whose native tongue may not be English). And I think, in many ways, that makes a difference in the way some sentences are worded by these authors. Again, if an author plans to sell in the American market, the book must be easily readable in English.

For Self-Publishers:

1] The very first page is your title page. Ideally, your title page font will be the same as your title font on the book’s cover. You may have to ask your cover designer for a copy of the title in the same font to be used on your title page.

2] Your copyright info always goes at the bottom of the page following the title page. Below, I made a sample copyright page that you can copy and paste, if you wish. I put (below) all the info you need to fill in. Just delete anything in brackets and put in the correct info. Of course, if you don’t plan to publish it in 2024, you’ll need to change the year.

**In the [name] space, if you use a publisher, their name goes there, but if you self-publish, you can either put your name or your business name. When you upload it into KDP, there is a place to put a publisher name. If you leave it blank, your sales page will say Independently Published, which I would do if you only list your name as the copyright. But if you use a company name, I would enter that.

Book Title Copyright © 2024 by _[name ]_

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

For information contact: _[email]_

Cover art by _[name]_

Stock photos ID: _[optional number]_

ISBN (paperback) _[number]_

ISBN (hardback) _[optional number]_

First Edition: [month & year]

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

3] Table of Contents:

Your table of contents goes on the page after your copyright page. Your ebook must have a table of contents that is clickable so the reader can click right to the chapter they want.

—First, put each chapter title (Chapter One) into Heading 1.

The way you do this is to go to the Home tab on the menu ribbon, then in the Styles box, right-click on Heading 1. A new box will pop up where you can choose how you want your titles to look. You can choose the color (the default is often blue, so I change it to black), the font, the size, left justified or centered, bold, underlined, etc. When you have it just the way you want, save it.

–Now, leave your cursor at the beginning of your chapter title(s), and click Heading 1, and it will change to your preferred title heading format. If you make any changes to the headings afterward, it will change all the formatted headings.

–When you are done, come back to the Table of Contents page and go to the References tab in the menu, then to the Table of Contents box, and click Table of Contents. You can choose the style you want, but it doesn’t matter. (Usually, the first 2 choices are titled Contents, or Table of Contents. Pick the one you prefer.) Then, EVERYTHING in your manuscript that is in Heading 1 will appear in your table of contents with its page number.

(You can change the font and/or size of the table text and the title by highlighting it and then changing it.)

If you make changes in the manuscript after this that change any page numbers, go back to your table of contents and hover your mouse over it or click it, and a little box pops up at the top left. When you click it, it asks you if you want to change just the page numbers, or the whole table. Click which one you want, but usually, you just need to change the page numbers.

Viewing an edited manuscript:

If you get back your manuscript and it is a sea of red letters and confusing text, but you want to see your work all in black and see it the way the editor does (I see no red), go up to the Review tab, in the Tracking box, and click where it says “simple markup.”

A drop-down menu appears. Click on “No Markup.” Now you will see it in all black as I do, or how the editor would see it. Of course, to turn it back on, just click again and put it back to simple markup. (Or all markup if that’s what you had before.)

Front and back matter:

Front matter consists of: the Title page, Copyright page, Table of Contents, Dedication, Maps or Pronunciation Guide.

Back matter is your: Acknowledgments, About the Author page, Also by the Author

There are two styles of writing called passive and active voice.

Passive voice says: Something was happening.

While Active voice says: Something happened.

This works with “had” as well.

Passive voice says Something had stopped.

While Active voice says: Something stopped.

Both the “was” and the “had” weaken the sentence. They are passive. We always want to write in active voice if possible.

Now, with the first example, using the passive voice would work if you are going to interrupt the action for something else. For example, “Something was happening, but she stopped to pick up something.” OR “Something was happening while something else happened.”

In that case, you are telling us that one action was happening and stopped or that something was happening at the same time as something else.

Acknowledgments:

Once you thank anyone who helped you, don’t forget to thank the readers and also ask them to leave a review–and put in a link to the book. You’ll have to do this after you’ve uploaded on KDP if you’re self-publishing. And if you’re going for a publisher, they will add it for you if you ask.

Hint: You do NOT need or want an agent for a small publisher, so if you are going that route, make a query letter, but instead of sending it to Top 5 agents, send it directly to the small publishers.

An agent is only there to:

1] get you deals you cannot get on your own

2] negotiate a complicated Top 5 contract.

In the case of small publishers, you can get the deal yourself, and they have a standard, non-negotiable contract (sign or don’t) with a little wiggle room if you want to ask for more books or a higher percentage, etc. Keep your 15% of the agent’s fee. (Having an agent with a small publisher does NOT get you a better deal.)

However, most small publishers aren’t worth losing the control of self-publishing because you won’t get to know your sales information, so if you run an ad this weekend, you won’t be able to see your sales info to tell you if it was effective, and more things like that.

If you aren’t going to go with the Top 5, which can be VERY difficult to do, I support self-publishing–if it wasn’t obvious. Lol. My non-fiction book shows authors how to self-publish on KDP and rank well, which means you get seen more and make more sales, which makes you rank higher… etc. It’s a cycle, and you’re either cycling up or down.

Here’s a link to that book if you’re interested: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B0C9STBQG7

For Poetry Books:

When we write poetry, there are a few things that we need to consider. First of all, it is not prose. (Not complete thoughts written in complete sentences, just chopped up.) Poetry is more like an artfully constructed stream of thoughts that either convey a scene, an emotion, a tone, or a story. Or a combination of them. We can punch up the poems by choosing powerful, emotive words.

Not to be too technical, poetry requires attention to sound, rhythm, rhyme, and format. Without a given structure, the poetry is called free verse. Poetry is, by nature, a contentious art, but even though some rules can be broken, it doesn’t mean they all can. (Rhythm and sound work best when you’ve got an effective format.)

To get more of what I mean here, read this article. I think it says what I want to convey: https://www.grammarly.com/blog/how-to-write-a-poem/#:~:text=Elements%20of%20poetry,obvious%20when%20you%20read%20poetry.

Poems (if you read that article I linked, you will see) are not just short paragraphs of full sentences. You want to use word tools to make it clever, concise, and expressive. You want to convey imagery and emotion with descriptive language. Stanzas break up when the subject changes or a thought ends and another begins. It’s like the pause of starting a new paragraph.

Part of the rhythm of poetry is using the lines to emphasize or focus on a word or phrase by breaking them. Use words with high impact, or rhyme, or a style. When I journal in poetry, I sometimes use full sentences that I chop up, though I usually write them with a certain style by chance, and then go back and make sure I’m using the words I want. Good poems need work and require editing.

It’s sometimes frustrating to get advice to work on your poetry and you think, “Well great. That’s how you say to write new poems, but what does that mean for the poems I’ve already written? I don’t know how to edit these.”

If I had a poem that I wanted to edit, I might go back to the beginning and step back to look at what my ideas were and start with the same concepts I have in the poem. Tweak or rewrite lines based on what’s already there. When I say to “work on poems,” what I do when editing poetry is to first check for capitalization, spelling, punctuation, ideas and concepts, structure, tenses, logical thoughts, then move on to choosing the best words.

And by that, I mean eliminating repetition that is not on purpose, using expressive words, making the meaning clear and concise, and using the most impactful words for the mood and subject matter to engender an emotional response.

The best poetry has the right combination of all these and is nuanced, if not complicated.

You can always make poems better with a few drafts, and I think you could put on your creative hat and hone them to bring the reader closer to the emotional experience–make it real for them and draw them in.

When people read poetry, as with any book, they want you to make them “feel” something, and they want to relate. Love poems are pretty easy to relate to, and those on heartache, pain, and loss. Decide what feeling you want a poem to convey, and then look up synonyms for words you have or change phrases to bring about an emotional reaction.

I find the best way to do this is to be confident and unapologetically honest about the feeling and maybe a little overboard on the severity of the emotion with creative language. Pay attention to the differences–they are subtle.

That’s all I have for now, but I’ll add more as I come up with them.

~jenn

Thanks for sharing your editor insight! I really like the idea to continue a scene from one chapter into another to keep people reading.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really works! Give it a shot. The books where I purposely did this have reviews stating, “I couldn’t put it down.” It’s the human need to finish the scene as well as a need to stop at the next chapter. That dynamic keeps the reader trying to find a good place to stop and unable to stop reading.

LikeLike

excellent material, Jenn.

I especially like that idea with the note cards — one simple statement for each scene and then re-arrange the cards if needed.

That would save me a lot of time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Jeff. I find it helps me immensely to be able to flip and write. I don’t worry so much about making sense or following the plan, I just write the scene it tells me to write and I know from my prep work that it will advance the story. I highly suggest it!

LikeLike